“I cannot unsee what I saw. I cannot unhear the cries and the screams that I heard and unsmell the smell of festering wounds.”

–Ghassan Abu-Sittah, A State of Passion

I wasn't expecting my hands to shake so much while watching directors and documentary filmmakers Carol Mansour and Muna Khalidi's documentary, “A State of Passion.” The documentary debuted at the Cairo International Film Festival in November 2024.

Mansour, the founder of Forward Film Production based in Beirut, has spent over two decades crafting internationally recognized documentaries that give voice to marginalized communities. Khalidi, who holds a Ph.D. in health policy, brings over 34 years of expertise in social development, enriching their films with thorough research and human-centered storytelling. Their recent filmography includes "Aida Returns" (2023), "Shattered: Beirut 6.07" (2020), and "Stitching Palestine" (2017).

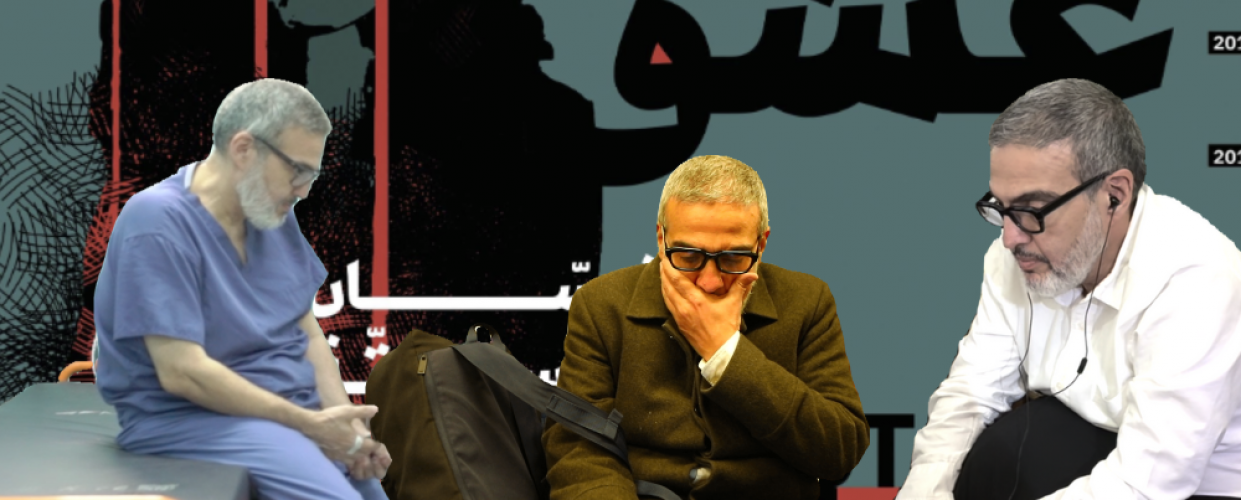

After working in the emergency rooms of Al-Ahli and Al-Shifa hospitals in Gaza for 43 days, as Israeli forces besieged the strip and millions of people living in it, British-Palestinian plastic surgeon Ghassan Abu-Sittah left. In the documentary, he says that he felt that there was nothing more he could do from a surgical perspective as there were limited resources and supplies. At that point, there were no fully functioning hospitals due to Israel's bombardment campaign.

On Dec. 22, I attended a screening of “A State of Passion” at the Metropolis Cinema in Beirut. It was followed by a Q&A panel. Right before the screening, Mansour and Khalidi introduced the documentary and reminded the audience that Kamal Adwan Hospital in Gaza was under siege at the time. The news was a gut punch to the stomach; Palestinians in Gaza were being murdered only a few hours' drive from where we were sitting in Beirut.

After months of witnessing the genocide in Gaza unfold on my dimly lit phone screen, and hearing the sounds of Israeli bombs echoing through Beirut, I thought I was prepared for this film. I wasn't.

The documentary opens with a screen scrolling through Google searches of Abu-Sittah, revealing that he was once most well-known for his expertise in being the only doctor in the United Kingdom who can perform the “scarless lip lift procedure. Less than twenty seconds in, we are violently jerked back to reality. A clip of a massive Israeli explosion rocks Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza, followed by the historic press conference hosted by Abu-Sittah and other doctors surrounded by piles of dead Palestinian corpses in front of the hospital massacre site. His eyes are frantic and hollow as he says, “We can see children's bodies piled up.” My heart feels like it's being torn to shreds.

This was not Abu-Sittah's first mission in Gaza. As he recounts in the documentary, his journey as a trauma surgeon in the besieged strip began in 1987 during the First Intifada. He returned just weeks after his wedding in 2000, during the Second Intifada, and again during each of Israel's successive wars on Gaza: 2009, 2012, 2014, and 2019 during the Great March of Return. He vividly recalls ‘Black Monday, which occurred in 2019, the night Israeli forces massacred 2,500 people in one night. Then, once more, in 2021 before returning again in 2023. A specialist in plastic and reconstructive surgery, he has dedicated much of his career to treating brutal war injuries and advocating for medical care in crisis-affected areas like Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, Pakistan, and Iraq.

Since the onslaught on Gaza began in October 2023, Mansour and Khalidi knew they had to act. When their longtime friend, Abu-Sittah, told them he was leaving Gaza – not because he wanted to, but because the hospitals had been bombed into dysfunction, leaving no supplies – they knew what they had to do. They would tell his story.

Originally, they wanted to title the film “The Reluctant Hero.” But true to form, Abu-Sittah wasn't comfortable with this role, as he never wanted to be portrayed as a hero. His life's work wasn't about himself, but about Palestine itself. Khalidi tells me that the title “A State of Passion” was inspired by Muzaffar al-Nawwab's poem, written in response to the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the siege of Beirut, echoing the relentless struggle for justice and resistance against oppression.

The filmmakers traveled to Amman to meet Abu-Sittah as he reunited with his family after enduring harrowing weeks in Gaza's emergency rooms, treating the wounded amid relentless devastation. These scenes of the three friends' reunions are especially poignant – both directors embrace him in long, silent hugs, a gesture that speaks volumes. No words are needed; the weight of his experiences and the depth of emotion are palpable.

They started recording him as soon as he was able. Khalidi astutely describes him to me, “Ghassan [Abu-Sittah] has the ability [to see] the bigger picture and position what he's witnessing within a historical and political and social narrative.” And that is exactly what this documentary does for the audience.

The documentary follows two threads, we see buildings bombed to dust, images and videos of trapped bloodied bodies, and listen to voice notes that Abu-Sittah had sent to family and friends while in Gaza describing the genocide in real time. We see bloodied bodies trapped in between slabs of concrete. Mansour recounts how difficult it was to comb through the footage when deciding which to include in the documentary, “You have to look at hours and hours of dead people, people running, houses being demolished, you know, the whole genocide. This was one of the toughest aspects of putting the documentary together.”

In one voice note at the beginning of the documentary, he recounts that doctors and nurses alongside him in hospitals in Gaza would arrive to work and find out shortly after that their entire families had been obliterated while they were gone. In another scene, Abu-Sittah recalls a time when he was operating on a teenage girl with broken legs, and the young woman's father told him: “I beg you. My wife and other kids have died. I have no one else but her.” Eight minutes into the documentary, a sense of hopelessness overwhelms me.

In a second thread, having reemerged from Gaza by the skin of his teeth, we watch interviews of Abu-Sittah and his family, including his wife Dima, his three sons Hamza, Soleiman, and Zaid, his only living uncle, the renowned Dr. Salman Abu-Sittah, and mother Jamal, as he navigates his relentless advocacy and justice work across London, Kuwait, and Beirut. The directors track his journey from Amman – often elusive and constantly in motion – to Kuwait, his childhood home, and back to his residences in London and Beirut. In each city, he immerses himself in efforts to raise awareness of the horrific genocide unfolding in Gaza, using every platform and resource available to amplify the urgency of the crisis.

The interviews with his family are extremely poignant – and offer small relief in the wake of the gruesome, devastating footage of the war on the people of Gaza. His mother charmingly laughs when one of the directors asks her if Abu-Sittah is her favorite child, saying that she will get in trouble because she is always accused of favoring him. In another scene, they ask if he was a mischievous child, and a look of love crosses her face as she describes her son who could never sit still, even in his youth.

In Kuwait, we ride in the car alongside Abu-Sittah as he takes us on a personal journey through the landmarks of his childhood – the home where he grew up, the abandoned lot he played football in, the school he attended, the street corner where he was hit by a car while riding his bike, and the clinic where his father practiced medicine. He was just fourteen when his father, with passionate certainty, told him he would one day follow in his footsteps and become a renowned doctor.

Through these intimate anecdotes of his upbringing, we gain a deeper understanding of Abu-Sittah's roots – of his uncles and father who were all displaced from Gaza in the 1948 Nakba, patriots who each played a role in the Palestinian resistance, both from within Gaza and abroad in Kuwait and the Gulf. His family's legacy, steeped in activism and medicine, is the foundation of his unwavering commitment.

Perhaps the most powerful scenes in “A State of Passion” are the intimate portrayals of Abu-Sittah in his home in London, preparing breakfast for his three sons. Interspersed between scenes of Palestinians being bombed, he hugs and kisses each of his children. When asked by Mansour if the children were frightened for their father's life, all three children insisted that they had faith he would return to them, safe and sound. Most importantly, they were proud of their father and completely understood why he returned to Gaza to save lives, time and time again.

Abu-Sittah, his wife, Dima, and their children all wear similar flannel pajamas. The audience witnesses a heartwarming transformation of how they know Dr. Abu-Sittah, from a renowned international physician rushing into dangerous crisis zones to perform lifesaving surgeries, to a loving, ordinary father and husband preparing breakfast and school lunches for his children.

In the film, Abu-Sittah's wife, Dima, emerges as a powerful witness and storyteller, her words and gaze carrying both sorrow and unwavering resolve. Her deep pride for Gaza is evident as she describes how it shaped her tenacity, giving her the strength to endure hardships others might find unbearable. She doesn't just grieve the genocide; she mourns the destruction of memories – the erasure of history. The home she grew up in, her grandmother's house – already bombarded four times in previous wars – was finally reduced to rubble in this latest assault on Gaza. And yet, with unshakable determination, she insists she will rebuild. This is the unshakable Gazan resilience she speaks of.

She has always stood by Abu-Sittah's decision to enter Gaza whenever Israel unleashed its brutal campaigns. For her, there was no other choice. “If he hadn't gone to Gaza, I don't know how I would have respected him.”

She explains, “My sense of duty is greater than my sense of fear.” A born and raised Palestinian from Gaza, she describes meeting and falling in love at first sight with Abu-Sittah in Gaza in the 1990s when he was volunteering in Gaza during the First Intifada. They got married during the Second Intifada, didn't have a honeymoon, and spent their first few months of marriage between Israeli invasions and Abu-Sittah's work in Al-Awda Hospital in Gaza. From the very beginning of their love story, it was clear that the Palestinian cause was at the heart of their partnership.

At the time of filming, many of Dima's family members remained trapped in Gaza – including her father, uncle, and her uncle's children. Eighteen of her relatives were murdered by Israeli forces in the early days of the war. In her interview, she recounts the terrifying reality her father faces – surrounded by snipers and tanks in central Gaza near the borders, cut off from desperately needed medication and food. Their conversations were rare, each one a fleeting connection amid the chaos. And whenever they did speak, his resolve was unwavering: he would rather die in his home than abandon it.

There is one scene of Abu-Sittah that is burned into my brain. In an interview with ITV News where Abu-Sittah is describing his experience in Gaza treating the injured, Abu-Sittah is crying and unable to speak. He barely can get the words out, ‘Someone has to pay.”

Grief, heartbreak, pride, rage, disbelief, and finally… A renewed determination. This documentary isn't merely about Abu-Sittah's bravery or dedication, but about Gaza itself. It is about the sheer determination of Palestinians in Gaza to pick up the body parts of their loved ones. To patiently sweep away the rubble of their homes and begin anew. And to remain in Gaza no matter what deterrent force tries to push them out.

Khalidi explains, “The message is that this is a huge injustice and every person should be examining where they stand on it and fighting this injustice with whatever tools they have at their disposal. We're asking you to speak up.”

My hands are no longer shaking when the credits of the film roll. Instead, I feel resolute. As long as Abu-Sittah and his family are still fighting for justice and Palestinians in Gaza stand proud and defiant on their lands, my hands won't shake.

The documentary has recently been screened at several events and film festivals. Check for updates if there will be a screening near you here.