Content warning: mentions of suicide and self-harm.

On Jan. 29, 2024, an emergency registered nurse (R.N.), Lana Abugharbieh, volunteered on a medical mission with an American-based Medical NGO in Rafah, Gaza. She was a part of the first group of medical mission volunteers with this NGO since the genocide began. Just before they arrived in Cairo, the mission team learned that Nasser Hospital medical center, where they were originally planned to be stationed, was under siege. At the time, four doctors from Chicago and one from Philadelphoa, who had already been at Nasser Hospital preparing patient assignments for the team's arrival, were evacuated to Egypt. The team Lana was accompanying was delayed by five days, making their journey into Gaza as soon as they were able. Once inside, they rerouted to the European Gaza Hospital as their ultimate worksite.

In late January 2024, medical teams were able to bring critical medical supplies and personal baggage into Gaza. The Rafah crossing had not yet been destroyed, and a certain degree of humanitarian aid and medical supplies were still able to reach Gaza. Since then, the conditions of Gaza's health care sector have rapidly deteriorated. Israeli authorities increasingly restricted who could enter Gaza, how many supplies they could bring with them, and destroyed the Rafah crossing, where medical personnel and aid were previously able to enter.

Palestine Square spoke with Lana as part of a series of testimonies documenting the experiences of medical professionals working in Gaza during the ongoing genocide. She went to Gaza on two medical missions, a year apart. This is Part I of a two-part interview with Nurse Lana recounting her missions. Part II, which covers her return to Gaza in February of 2025, is forthcoming. (Link to be updated here and on the blog)

Lana Abugharbieh is an emergency and trauma RN of Palestinian descent, based in the Washington, D.C. area in the United States. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Nursing. Though Lana originally planned to join a medical mission in March, her skills and experience were required earlier, so she joined a group in January instead. This was Lana's first international medical mission. She worked in Gaza for 10 days, from Jan. 29 to Feb. 8, 2024, at the Mohammed Yousef Al Najjar Hospital, the MedGlobal/HCI (Human Concern International) field clinic, and the European Gaza Hospital. The Najjar Hospital has remained out of service since May 2024 and was severely damaged by Israeli shelling in November 2024.

This interview was conducted on Sept. 24, 2024, several months after Lana's return to the U.S. Nurse Lana discusses the dire state of Gaza's medical sector, provides detailed accounts of the injuries she treated, and sheds light on the devastating effects of Israel's bombing, violence, and restriction of humanitarian aid on Palestinians, calling for a ceasefire as the only practical solution to improve health care across the strip.

This interview has been transcribed and edited for clarity and brevity.

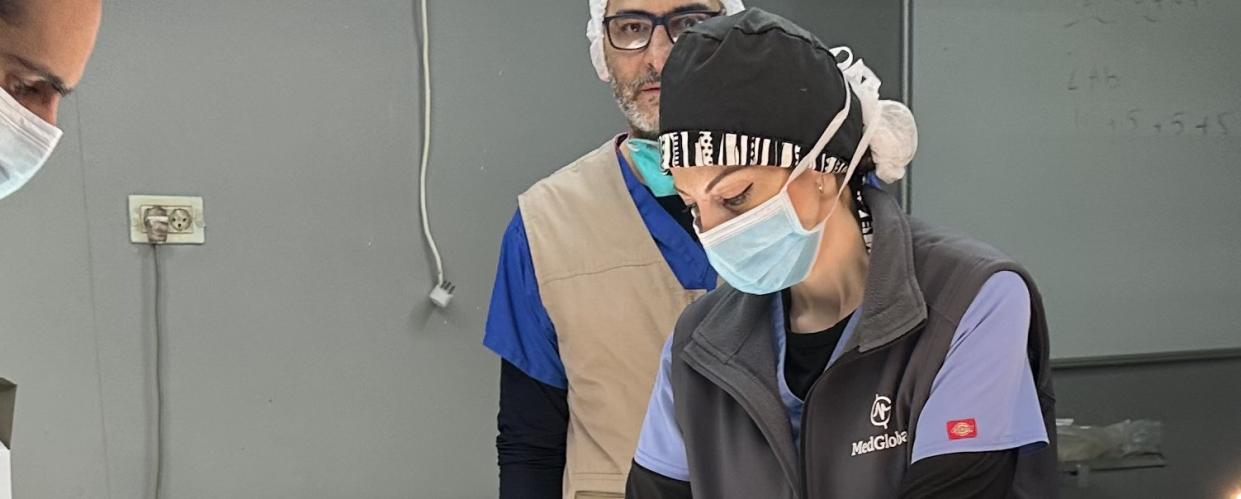

Image courtesy of Nurse Lana Abugharbieh.

What was your experience entering Gaza for the first time?

Driving into Rafah felt like forever. I just wanted to hurry, be there, and do work. We had to stop at eight checkpoints along the way. In about three out of the eight checkpoints, Israeli soldiers gave us a hard time, making us wait a while. We were almost turned around at one of our final stops, but after some pleading, they let us in. I was able to bring 200 pounds worth of supplies with me, including equipment, bandages, and medications. By the time we got through the Rafah crossing, it was dark, which initially made me a little nervous, because COGAT (the Israeli agency, Coordinator of Government Affairs in the Territories), does not permit any driving at night. As soon as we arrived at the border, they had us run our baggage through X-ray machines. 10 minutes in, the power went out. It was pitch dark inside, pitch dark outside, and the only sound was that of really loud drones. The power came back on around 10 minutes after that, but I had honestly thought, “Are we about to be attacked?”

The drones were the first thing I heard. There were times when they would get louder, and you think they must be getting closer, so you become nervous. At that point, I only thought there were surveillance drones hovering around us, not attack drones. Had I realized they were also assault drones, I would have panicked at that moment.

As we drove to our designated safe house in the Mawasi area, I saw tents everywhere and children running around. Even with the bus windows closed, the overwhelming odor of diarrhea filled the air. The Gaza Ministry of Health had reported over 8,000 cases of Hepatitis A, along with suspected cholera, which explained the unbearable smell. Because I was part of Group One on the medical mission, we followed strict protocols — we were only permitted to travel between the safe house and the hospital. We weren't allowed to venture into the tent areas, so I never entered them. Each day, I saw rows of tents lining the roads as we drove to the hospital. Thousands of people had set up shelter in and around the European Hospital, believing it was the safest place to be.

Image courtesy of Nurse Lana Abugharbieh.

How prepared do you think you were for the experience, and how did you and your team learn to adapt to the conditions?

Before the medical mission, I was working in the Baltimore Shock Trauma Operating Room, so I'm used to seeing really bad injuries. However, the injuries I saw in Gaza were different. I had never seen shrapnel injuries before. So many people had shrapnel freckles all over their bodies. The wound sites were hot to the touch and necrotic-looking wherever the shrapnel was embedded. What I honestly wasn't prepared for was realizing how much privilege we have in the U.S. with our access to all the medical supplies, equipment, medicine, and staff that we need. In Gaza, you have to get creative. I had to come up with ways to provide wound care discharge instructions. How could I tell people to “go home, keep your wound clean and dry by washing it with mild soap and water and then rewrapping it with clean bandages” when my patients were returning to tents with no running water or soap?

Where was your first assignment? Were you forced to move to different hospitals throughout your time in Gaza?

On the first day, we went to the Najjar Hospital in East Rafah. It honestly felt more like an urgent care facility than a hospital. It contained 60 beds and almost no supplies, no CT scan machines, and only a few ORs. Despite these conditions, there were about 300 patients admitted at the time of our visit, leaving the emergency room completely overwhelmed. The lack of sufficient medical personnel, supplies, and equipment made it impossible to care for everyone.

One case in particular stood out to me — I attended a man lying unresponsive and just hours away from death. His companion informed me that he had been lying on the ground for 10 days without being assessed. His bladder was so distended that it appeared as if he had a large tumor in his abdomen, and his muscles were twitching from severe electrolyte deficiency. We inserted a catheter and drained about two liters of urine, which immediately flattened his stomach. After administering IV fluids, he slowly began to regain consciousness. It was a heartbreaking situation. Often, quieter or unresponsive patients are the most critically ill, but in such a crisis, the screaming patients — those with shrapnel injuries, lacerations, and broken bones — tend to be prioritized first. Triage in this environment means making difficult decisions: evaluating the sickest, prioritizing care, and doing the best you can with limited resources.

Image courtesy of Nurse Lana Abugharbieh.

My team and I attempted to assist in the operating room, but the surgeon told us there wasn't enough room, nor were there enough supplies, so we had to shift our efforts to other medical facilities where we could be of more help. The following day, our team moved to the MedGlobal/HCI field clinic in Tal Al-Sultan, and I worked in the wound care section.

We did that for two days, and then we went to the European Gaza Hospital for the rest of the time, where I worked in the operating room. At EGH, we unfortunately could not sedate all the patients we saw because the hospital was running out of anesthetic drugs. We resorted to performing nerve blocks (like epidurals) to numb patients from the waist down to perform lower limb surgeries. The surgical instruments were filthy, and we [had to] reuse them from patient to patient. One hundred percent of the patients I saw in the OR had infections. The conditions were unimaginable.

Image courtesy of Nurse Lana Abugharbieh.

Although there was an extensive range of injuries, what were some of the more common injuries that you saw and treated?

At the MedGlobal/HCI field clinic, where I did wound care, I saw a lot of shrapnel injuries and burns. It was winter and freezing at the time, and a lot of children would accidentally fall into the campfires they started. Also, most people had no time to escape bombs, so they would run out of their homes barefoot, and end up with cuts on their feet that got infected. We also did a lot of wound care for infections around external fixators — medical devices with pins, rods, and screws placed externally to help stabilize broken bones.

There were lots of lacerations, too; some even self-inflicted. I had a 27-year-old patient who slit her wrists in attempt to commit suicide. Her mom told me, "Look what she did. She wants to hurt me even more. I'm already hurting." I spoke with her daughter and told her, "You're a beautiful person, and you're wanted. Look how much your mom wants you here. Your siblings want you. You have a lot to offer. Don't give up. You can be a voice for the people who feel like you, too. You can encourage them." I suggested she reach out to other girls her age who might be going through the same emotions, reminding her that she could be a strong and inspiring voice for them. By the end of our conversation, she seemed genuinely motivated, smiling brightly, and she gave me a big hug. She even came by the clinic the next day, and gave a smile and a wave. Morale is low living in those dire conditions in Gaza. Many are at their wits' end with what's going on, especially those with children. Everyone is frustrated, afraid, and in survival mode, so no one has patience. I realized this patient just needed someone to talk to.

Image courtesy of Nurse Lana Abugharbieh.

Being a Palestinian and having visited Palestine before, what was it like being in the middle of the genocide, under fire, and watching the level of destruction that your people are having to undergo?

Naturally, being Palestinian, this was personal, and it hurt. Although if I were in any country and I saw that this was happening there, I would feel the same way. It was terrifying for sure. Every night and every day. At the beginning of the trip, I would hear bombs drop by the hour, but near the end of my stay, the bombs were dropping every 15 minutes, and the drones were in constant buzzing. Knowing that every time a bomb drops, there's going to be mass casualties and deaths, you cringe with every sound. I also felt a lot of guilt being in a safe house because I had a roof over my head, access to a stove, and running water. Seeing everybody displaced and homeless was just heartbreaking. But I also saw their resilience; how they cooked in clay ovens, charged their phones with solar panels, sold goods outside of their tents, and grew fruits and vegetables in greenhouses. They were trying to survive to the best of their abilities, which honestly made me feel proud.

What was it like transitioning back into life here in the U.S. once you came back from your medical mission?

I'll admit, on my first night back, a plane flew low overhead and I woke up startled, thinking it was a fighter jet like the ones that constantly flew over us in Gaza. On the second night, someone must have slammed their car door, but to me, it resembled the sound of a distant bombing. The two nights I was back, I would wake up disoriented, thinking I was still in Gaza. After that I adjusted fine. I had to immediately go back to work, and didn't have time to process.

I gave about eight talks per month during the first three or four months after I returned. As much as I dislike public speaking, I never turned anyone down. The women in Gaza had asked me to share their stories, pleading with me to let the world know what was really happening. They felt unseen, believing that no one outside knew the truth and that Western media was distorting their reality. They told me, “Please go back and tell them the truth. Tell them what's happening to us.”

It wasn't until three or four months after the mission that I truly began to grasp the idea of what I had witnessed in Gaza. I realized I had been in the middle of a genocide, but I hadn't been able to process it because life had been so hectic. Since returning, I've had a few sessions with a therapist, but honestly, they haven't felt helpful. What I find most therapeutic is talking with other medical professionals who've been there. There's a sense of a shared understanding — a trauma bond. We saw the same horrors, and we lived through what was, without question, a genocide.

Image courtesy of Nurse Lana Abugharbieh.

If the circumstances allowed, do you imagine yourself going back to Gaza at a different stage? We don't know what the future holds, we don't know what the rebuilding process would look like, but do you see yourself conducting work in Gaza again?*

Since returning from my mission trip, I've had three opportunities to go back, and I would have gone back immediately if it weren't for the toll it would take on my family. They told me, “We died a hundred deaths while you were gone.” As terrifying as it was to be there, with the constant fear of bombardment as the hospital and safe house shook from the blasts, I would still go back. More than anything, I want to show the people in Gaza that they are not forgotten. There are people who care deeply for them, and that humanity still exists.

As you've mentioned, it is incredibly important to continue to share these stories and give a voice to Palestinians in Gaza. Is there anything else you feel important to share?

At this point, my message is simple: we're just putting Band-Aids on gaping wounds. Even allowing aid to enter isn't enough. It's not solving the problem. You can't treat burn wounds while the fire is still blazing. We have to stop the destruction first. The reported death toll is over 40,000 [at the time of this interview], but in reality, it's far higher — easily over 200,000. Countless people on dialysis have died because they haven't been able to get dialyzed; cancer patients who couldn't access chemotherapy have lost their lives; cardiac patients have been without meds for a year now, they've lost their lives; and every injured patient who got septic, died. The number of casualties will continue to climb at a rapid rate if we don't stop this atrocity. We need a ceasefire now.

Image courtesy of Nurse Lana Abugharbieh.

The following are journal entries Lana documented on Feb. 3, 2024, during her medical mission. This personal record reflects on her experience of conducting work in Gaza under Israel's constant bombardment.

Around 5:00 p.m.:

Five bombs just dropped near the hospital. I'm afraid. I know this is the finale.5:45 p.m.:

3 more bombs dropped and shook the hospital. I'm TERRIFIED!!! I was going to sleep in the hospital, but I don't know if it's a safe place. Look at what they did to every other hospital!6:15 p.m.:

Got the green light to leave the hospital and go back home, but is home even safe? There is NO safe place in Gaza. Calling a group meeting tonight to see if I can get everyone on board to ask to go home!8:46 p.m.:

I feel defeated! It's pointless being here. It's a helpless and hopeless situation! The health care system has completely collapsed! There are 1.9 million internally displaced people in Rafah! People are going weeks without being seen or even triaged in the hospital! The hospitals have become a shelter. There are literal tents everywhere in the hallways of the hospitals! Only a few hundred doctors/nurses to 70,000 injured people in ONE TOWN! It's truly an IMPOSSIBLE SITUATION! People will die from injuries that are 100% survivable because they can't get seen for days/weeks. Everyone's wounds and surgical sites are infected and they'll get septic and die. They don't have enough supplies, they don't have enough meds, or staff! It's a death sentence for the wounded. So what's the point?! Why even try?! The ONLY way we can help is if there is a permanent ceasefire and we bring in plane loads of staff, meds and supplies!!!

*Editor's Note: Nurse Lana did return to Gaza in February of 2025 during the short-lived ceasefire. She discusses her second mission in Part II of this interview, which will be forthcoming on our blog.

Parts of this interview were updated after publication to reflect the accurate sequence of events.